My observations are based on 30 years military experience and in particular draw on 13 months in 2016/17 as the Deputy Commander of the US-led coalition that defeated ISIS (Da’esh) in Iraq and Syria. The deployment coincided with the 9-month battle to liberate Mosul, Iraq’s second city, (arguably the most significant urban battle since World War 2) and the 6-month battle for Raqqah, the capital of Da’esh’s so-called caliphate. These battles combined some of the most sophisticated technologies available to any militaries on the planet, delivered by the US and her allies, with tactics and equipment that were decades old (largely delivered by the Iraqi Security Forces and our Syrian partners).

There has been extensive commentary about the inept performance and ill-discipline of the Russian military in Ukraine; some better informed than others. However there has been rather less discussion examining just how difficult it is to successfully orchestrate the full panoply of the 21st Century arsenal (combined arms manoeuvre) amid the chaos and confusion of war. It is exceptionally hard. There is no more challenging or complex human endeavour than prevailing in battle; anyone who thinks that there is, has clearly never set foot into the theatre of war. So criticism of the Russian performance is justified, but their woes should serve to remind us of how hard it is to fight and win; there are cautionary lessons here for western militaries.

Technology has arguably only made the plight of the soldier harder as enemies enjoy the same advances, making many tactics obsolete and technologies vulnerable. However, there are no absolutes in this. Judgements that images of destroyed Russian armour confirm the death-knell of the tank are likely premature. Rather, they act as another reminder that the different arms of war must be operated in concert with each other; tanks without infantry, artillery, engineers and air support will be destroyed. Fought together, they will likely remain an invaluable part of army inventories for some time yet.

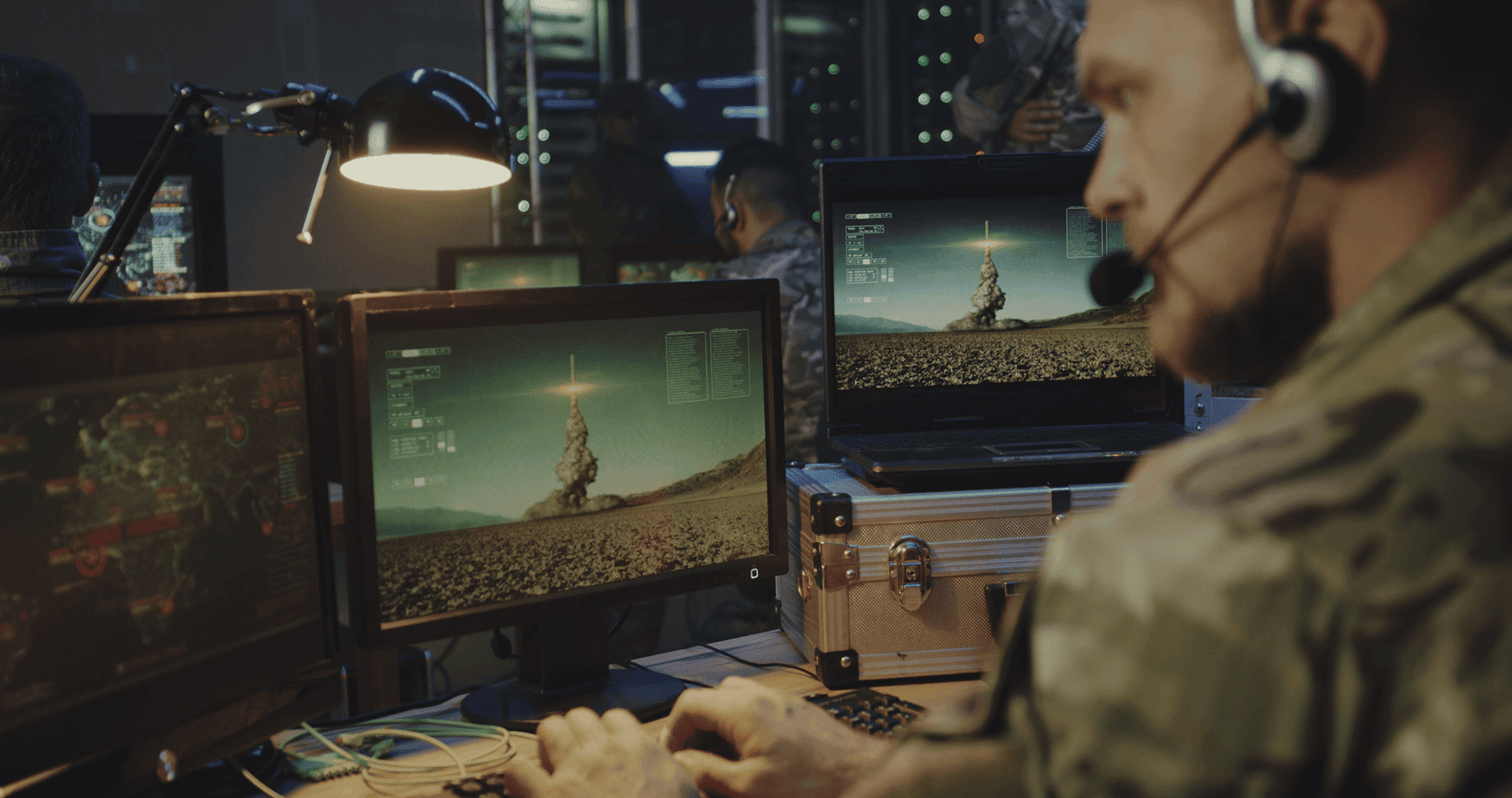

General Sir Patrick Sanders, who leads UK’s Strategic Command and will shortly take over as head of the British Army, said last year in a speech that he had ‘more need of Q, than I do of 007 or M.’ There are few, if any, more shrewd and capable people in uniform today than Sanders and drawing from James Bond ensured a clever and quotable sound-bite. He was making a much-needed rallying call for Defence to do much better at attracting and harnessing digital warriors. The modern battlefield needs data engineers, cyber operators, and computer programmers every bit as much as traditional combat warriors. The British military, along with our friends in America, Canada, Australia and elsewhere, are wrestling with this challenge. How can they attract digital warriors in a highly competitive employment market, and how can they ensure that they are valued and hold equal status to the traditional warrior?

Today’s battlefield is a complex mix of old and new. It is in the public domain that we used offensive cyber against Da’esh in Syria to degrade their powerful media architecture. It was a ground-breaking operation designed and executed by some of the best cyber operators in the world, and yet it was never going to be decisive. It formed part of the important shaping operations to set the conditions for kinetic operations. Similar highly sophisticated techniques were used to degrade the defence of Mosul. However, these cutting-edge efforts did little to improve the experience of the Iraqi soldier grinding his way through the city, clearing bloody building after bloody building. There was nothing ‘James Bond’ about the hell he operated in; supported by coalition airpower and artillery, his nightmare would have been readily recognisable to troops fighting in Stalingrad. The final defence of Mosul shrunk to a tiny perimeter in the Old City, cleared by brave Iraqi soldiers armed with bayonet and grenade crawling through the rubble, more reminiscent of 1942, than 2022.

Western military strategists talk extensively about their aspiration to avoid war in cities and about how technology can give us the edge. The reality is that war is, and has always been, about people, and so cities will retain their magnetic draw on the fight. We are seeing this in Ukraine and it was the same in liberating Iraq where the campaign was a series of urban battles: Ramadi, Fallujah, Mosul, and Tal Afar, among others.

Today’s militaries require a subtle mix of conventional and digital warriors. On the front line young men and women are needed who can endure the brutal nature of war, as old as the hills, while exploiting the best technology we can give them; as comfortable with their rifle as with situational awareness applications that aim to give them an edge over their foe. Equally, militaries must compete for the attention of the most digitally talented. These young people are in high demand and understand their value to employers. They are readily drawn to tech companies, but our Armed Forces can offer fulfilment and purpose that is in short supply elsewhere. The challenge continues to be how to persuade enough of the right people to see a career in uniform as being something to consider. This is not easy and more compelling narratives are needed, together with building Defence’s technical reputation.

Additionally, we often do not recognise the potential of those already working with us. Aptitude testing frequently highlights the greatest digital potential among those we have under-estimated. Identifying and harnessing potential and initiative offers great value.

The Australian digital skills start-up, WithYouWithMe, who have recently launched into the UK with a refreshing and disruptive mindset, are helping British Army regiments to do just this. One regiment recently put every soldier through WithYouWithMe’s aptitude testing, offering the commanding officer invaluable insights into the potential skills at his disposal. The firm is now delivering a free 6-week digital bootcamp to turn their potential into digital skills, allowing the regiment to compete more effectively on the battlefield.

Events in Ukraine have acted as a stark reminder that we can ill-afford to take national security for granted. Partnership with industry will be key to assist our Armed Forces to digitally transform, while retaining the hard-edged skills that have secured victory on battlefields from Normandy to the Falklands to Kiev.

This article is laced with contradictions which reflects two things. Firstly, that there are no binary answers between the need for hard-edged tools and techniques of war, and the digital arsenal to prevail in the digital combat arena. Secondly, that this is a complex issue, demanding debate and collaboration. I would really welcome insights and invite you to subscribe to my articles to continue the conversation.

Learn more about how you can source, recruit and deploy diverse new talent into your organisation or find untapped talent within your existing workforce. Explore Discover Potential.